Myanmar IP Guide 2025

05 November 2025

Trademarks

Intellectual property is not a widely known topic in Myanmar. The four subjects under this heading – trademark, copyright, industrial design and patent law – have been introduced to the public in our historical collection of laws known as the Burma Code through the 1914 Copyright Act and related laws. The four laws were drafted again in early 2010s; it took nearly 10 years for the laws to be enacted in 2020 before they came into force in 2021.

When the new laws came into force, the next step was to allow all the previously registered trademarks under the old system to be refiled at the newly opened Intellectual Property Department (IPD). In 2022, the IPD gave online training courses in trademark filing to anyone who had a basic first degree, the equivalent of a Bachelor’s degree. It was a five-day course and a certificate was awarded, after which only persons holding these certificates were eligible to represent clients who owned the trademarks to be refiled.

There are set out conditions and documents that are required to be filled in and completed to officially be represented at the IPD for refiling. The IPD also trained an estimated 60 officers from their office as examiners and senior examiners to examine applications and attached documents.

Trademark registration

Applicants will have to pay fees after the application and examination towards publication at the IPD office. Any member of the public who has interest in the relevant mark may submit a written opposition/objective. A period of three months is allowed to file an objection. If there is no objection, the IPD will proceed to register the trademark. After the mark is given a permanent registration number, the owner of this mark may take action against any contradictory marks or infringements.

The period for appeals are given in various steps under the trademark laws.

If respondents/defendants are not satisfied with the final results of the IPD, they are allowed to proceed to legal action at the IPD-designated court. The judges in this court are well-trained and deal with IP cases based on the Trademark Law of 2020.

The Trademark Law itself is quite comprehensive. However, there are weaknesses in the examination system, especially the interpretation of the examiner. Laws are enacted to offer justice and comfort to the stakeholders whose rights have been infringed and losses affecting the stakeholder’s business. Every alleged infringement is complex, and it will take some time and experience to resolve the disputes along the way before the registration is finally approved.

The Trademark Law and the IPD have created a system and established an office with trained officers to ensure or prove to the trademark owners that the laws will protect their ownership rights. They are encouraged to promote their businesses by registering their inventions and creating trademarks, by way of using work marks, design marks, coined marks, sound marks, smell and all other methods they can find to use on their products and services to be outstanding, new and different, in their own community, countrywide and worldwide.

Most of the people in Myanmar are simple to the point of being naïve by ignoring or not having the knowledge that they have rights and laws to keep their trademarks protected from unauthorized or illegal use. They somehow feel proud that the public likes their trademark more than the product or services and do not realize that unauthorized use, exact copying or acquiring it illegally will affect their business. If they do not register it with the IPD, it is hard to stop infringement later. Their proof may be to show their original ownership with long-term use, but under the new Trademark Law, only evidence of registration at the IPD will prevail.

The general public are still not fully aware of the functions of the IPD, although the laws have been in force since 2021. Most of the applications are done online by trademark agents and IP lawyers. However, there are guidelines for the individual trademark owner to apply for registration at the IPD office, physically, without engaging agents or law firms.

It is a lengthy process and the IPD has conducted several training courses, mainly for agents and lawyers, on how to submit registration of trademark ownership online. This article addresses the basic steps that an applicant needs to go through to get the trademark successfully registered with the IPD. There can be instances that either the applicant or the examiners interpret the rules and regulations differently and could prolong the process, due to requiring appeals against appeals and rejections from officers or examiners due to improper filings or misinterpretations.

The IPD is operating with officers and staff to make the system work and allow the rightful trademark owner to get the ownership legally registered. However, there are always reasons for dispute and offices within the IPD that work to resolve the true identity of ownership. If for any reason an amicable resolution is not achieved, the dispute can be taken to a court of law. Currently, there is only one court with two trained judges to hear IP cases if mediation cannot achieve justice.

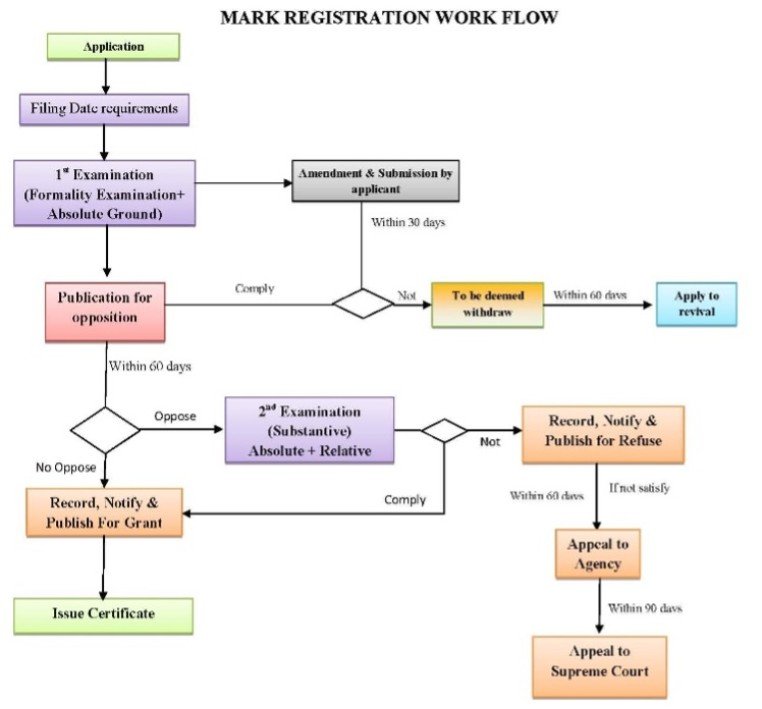

Figure 1 highlights the different levels of the IPD registration of trademark system.

Figure 1: Flowchart of Trademark

Figure 1 shows the trademark registration application process as a flowchart image from the IPD website.

Implementation of IP laws

Amongst the four IP laws, although the implementation of the Trademark Law has been initiated, there is a gap in the timeline between the enactment and the implementation, or lack thereof, of the IP laws due to the Covid-19 pandemic and political instability in Myanmar after the pandemic. Therefore, since none have been fully implemented with the exception of some aspects of the Trademark Law, this lack of implementation hinders effective IP protection in the country.

Patents

Myanmar’s law on patents has been enacted but has yet to come into force, as no rules and regulations have been drafted or completed for enforcement. Creators and inventors should apply for patents in countries outside Myanmar, as Myanmar does not yet have qualified examiners for complex inventions, especially in medicines, artificial intelligence, computer software, etc.

Copyright

There has been significant progress with the full implementation of copyright protection in Myanmar, however there are still areas that need to be addressed and criteria that are lacking and which can be improved upon through research, such as the recent copyright infringement with the use of artificial intelligence.

The current copyright laws of Myanmar was enacted on May 24, 2019. After more than a decade of drafting laws, the actual publication of the Copyright Law in the local Myanmar language is interpreted as laws to protect “literature and arts.” Enforcement of the law became active in 2023.

A wider explanation is given under related rights – the exclusive rights of authors and artists – that includes performers of music, singers, audiovisual and cinematographic works, films, traditional cultural expressions, narratives, symbols and other original creations.

Protection under this law has become limited after the invention of computer programming and now the introduction of artificial intelligence, which only the most developed countries are prepared for.

Chapter 2 provides the objectives of enforcing the copyright laws; however, it can be seen in Chapter 3 that the Union Government needs a Central Committee formed by various ministers from the government to ensure that protection is given to all right holders within the boundaries of law and not just on the law itself, which is rather limited and yet to be tested.

Chapter 8 provides protection for a list of copyright subjects. Yet again, Myanmar has a long way to go to catch up with many of the latest inventions and creations of man-made tangible and intangible products.

Chapter 10 discusses the economic rights and moral rights of the owner/creator of the copyrighted material. Laws are only guidelines, and when an issue involves man-versus-machine, the problem will be deeper and more difficult to resolve. Experienced examiners, intellectuals and mediators must be included to resolve and interpret the issue. Since Myanmar’s intellectual property laws are at an early stage of development, expert advice or assistance is needed from WIPO as well as other more experienced IP organizations around the world.

Chapter 16 provides for the registration of copyright and related rights that is not compulsory. However, the law lacks the ability to impose the proper criteria required for the Registrar to accept the applicant’s work as his own creation without registration as evidence. Even without objection at the time of application, more investigation is needed before copyright rights are awarded, especially in literature and music as Section 54 of the Copyright Law again confirms that creators and owners of copyright will enjoy their rights under this law with or without registration.

Chapter 19 clearly gives copyright owners the right to form a collective management organization on copyright and related rights. It likewise gives official approval to form an organization with experts who understand and can identify copyright infringement more readily than the officers and employees of the registration office.

Enforcement of copyright laws

Chapter 20 states The Supreme Court of the Union allows establishment of Intellectual Property Courts and the appointment of judges.

Chapter 22 provides the right to stakeholders of the rights to pursue their loss of rights and grievances under a civil miscellaneous case. When it comes to providing justice and remedying the losses and rights of copyright owners, the IP courts are still in their infancy, especially when calculating the quantum of compensation to be awarded. One needs to apply provisions of the Evidence Act, Criminal Procedure Code, Civil Procedure Code and other relevant existing laws to ensure that appropriate relief is awarded to the party whose rights were infringed. Currently all disputes are being amicably settled out of court as parties on both sides of disputes are not prepared to disclose settlement amounts.

Chapter 23 provides penalties for various types of offenses. Cash fines are low and do not reflect the actual damages or losses involved. For imprisonment terms not exceeding three years, the judge would order penalties depending on the seriousness of damage that the copyright owner suffered. Once more, these sentences have not yet been authorized under current laws.

Overall, copyright infringements need to be researched more, particularly with the introduction of artificial intelligence readily available on the internet with both free and paid access. AI will make it more difficult to discover the real infringer or the real source of copyright ownership, especially when the source of such information refuses to take any responsibility for the information they provide online.

Despite its shortcomings at present, having a Copyright Law is the right step towards protecting the rights of creators; slowly but surely, everyone will come to recognize and accept the laws in Myanmar.

Industrial designs

Creativity contributes to the progress of a country.

Inventions alone are not enough; a good design achieves the public interest and a desire to acquire a novelty. Good design motivates the creator to improve his own work and those of others lacking in function. Hence, countries need to reflect on the importance of design creativity that will improve their image abroad and keep them on a competitive level with other developed countries.

Myanmar’s recognition and implementation of industrial design laws may be slow, but with so many influencers worldwide, it is not too far behind to recognize the benefits of enacting the laws to benefit the country as well as inventors and creators.

Myanmar’s industrial design laws were enacted in January 2019 and brought into force in October 2023. In the past, there have been no known applications for the registration of industrial designs in Myanmar from outside the country. The first applications were accepted in February 2024; examinations have been rather swift without too many oppositions or appeals. In the first year of its existence, there were around 30 industrial designs registered.

The Industrial Design Act of 2019 has 24 chapters. Chapters 3 to 6 are mainly administrative but are important to define who and what roles the officers of the Intellectual Property Department of Myanmar play in protecting the rights of applicants as right holders of their creations. It must be noted that the duties of the officers appointed are many and it is hard to come across well-trained officers in Myanmar. Yet, the laws are encouraging for creators and a deterrent for infringers, who take advantage of ignorant priority right owners.

Chapter 7 of the act provides requirements for registrable protection of industrial designs. Chapter 9 provides avenues for persons to file for industrial design registration. Chapter 13 provides priority rights to an applicant for six months from the filing date of registration based on special terms and conditions.

Chapter 14 provides the protection term of five years after registration, limited to renewing twice every five years. Overall, an industrial design can be protected for 15 years from the date of initial registration.

Chapters 15 to 17 provide for exclusive rights of registered designs, transfer of rights and prevention against third parties from enjoying the same rights of the owner without the owner’s express consent. It allows the legal owner of an industrial design to file a lawsuit against an infringer of the rights of the registered industrial design in a civil action. It also provides for the transfer or license of the registered industrial design to any other person in accordance with the provisions in Chapter 16 and 17. If the registration is filed jointly and owned by two or more owners, each individual will have an equal and undivided share in the industrial design rights in the transfer to another party.

Chapter 21 provides for the special IP course established by the Supreme Court of the Union. Chapter 22 addresses the authority of the IP Courts.

Chapter 23 provides penalties for infringement and grounds for deciding penalties for infringement. Grounds for deciding penalties are not precise enough, but if the infringed owner wishes to appeal further beyond the IP Court, the owner can file up to the Supreme Court, the highest in the country.

Chapter 24 provides for miscellaneous actions beyond rules and regulations, if any party is adversely affected. Infringement of registered industrial design disputes between two parties may be settled by the means of mutual understanding, arbitration or judicial proceedings.

Sections 84 and 85 give the aggrieved party an idea on what to expect from the relevant ministry and the lengthy procedures that will be applied to get justice served.

Enforcement

Myanmar faces several enforcement challenges in its intellectual property regime, despite recent legislative progress.Here’s a summary of the key issues:

Although Myanmar has enacted four major IP laws covering patents, trademarks, copyrights and industrial designs, theimplementation infrastructure remains underdeveloped. The Intellectual Property Department (IPD) is still in itsformative stages, and many enforcement mechanisms are not fully operational.

Specialized IP courts have been designated, such as the Kyauktada District Court and High Court of the Yangon Region,but they are still building capacity in terms of trained judges and procedural clarity. Enforcement agencies like customsand police lack technical expertise in identifying IP violations.

IP litigation in Myanmar can be time-consuming and procedurally complex. Cases often take months or years to resolvedue to overburdened courts, lack of judicial precedent and specialized legal expertise and ambiguities in the newlyimplemented laws. While civil remedies such as damages and injunctions are available, courts often require extensiveevidence of infringement, proof of actual harm or loss and security deposits to prevent misuse of provisional measures. This can be burdensome for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) seeking justice.

Even though provisional measures (e.g., injunctions, evidence preservation) are available under the patent and trademarklaws, they require substantial documentation and may be revoked if civil proceedings are delayed.

Additionally, there is limited understanding of IP rights among businesses and consumers, especially in rural and informalsectors. This leads to frequent unintentional infringement, weak demand for formal IP registration and difficulty inproving damages or establishing ownership in court.

Myanmar’s customs enforcement of IP rights is still evolving. While the law allows for border measures to prevent theimport of infringing goods, implementation is inconsistent due to lack of coordination between IP authorities andcustoms, limited training of customs officers and an absence of a centralized IP database for verification.

Myanmar has transitioned from a first-to-use system (based on common law principles) to a first-to-file system under itsnew IP laws. However, legacy practices and ongoing legal reforms create confusion, especially in trademark disputeswhere historical use may still be relevant.

Establishment of the IP office

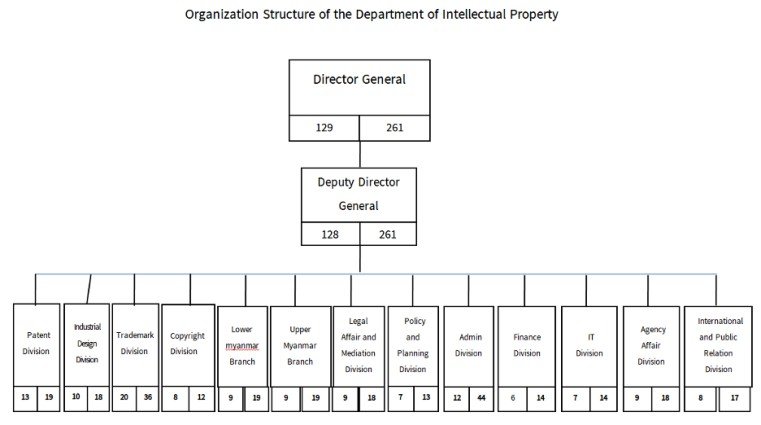

To support and promote the implementation of the IP laws which have been promulgated, the Ministry of Science and Technology held two meetings in May 2013 and August 2014. A draft report on establishing Myanmar’s Intellectual Property Office (IPO) was developed based upon the discussions and an organizational structure for the IPD was designed under the Ministry of Commerce. Thus, with the enactment of the IP laws promulgated in 2019, the Ministry of Commerce became the focal ministry for implementing IP laws. The organizational structure of the IPD shown in Figure 2 was established on December 23, 2020. The numbers shown represent the male-to-female ratio within each division as of late 2025.

Figure 2: Organization Structure

Figure 2 shows the organizational structure of the Department of Intellectual Property from the IPD website; the numbers represent the male to female ratio within the committee

IP policy and strategies

The IPD has a vision to support and raise intellectual property awareness and human resource development by establishing and modernizing the development of the Intellectual Property system. By encouraging IP utilization, the IPD aims to promote innovation and creation under the protection of IP while strengthening regional and international IP collective effort against infringements.

Up to this year, there have been about 40,000 old marks which have been refiled for examination; more than 7,000 have been registered, passing the examinations successfully. New marks are also being applied for and, for straightforward cases without any objections from a third party, they are duly registered within six months. There is, though, room to make Myanmar’s Trademark Law and registration more efficient, with the help of WIPO and educators by holding awareness programmes on how and why trademarks should be protected, and their unique position in alleviating the country’s image, GDP and trading rights with the rest of the world. Myanmar is one of the few countries that have recently come into the fold of creating IP laws that will encourage foreign businesses to trade with the each other in good faith without deep concerns about violation of their IP rights, which will be protected by the Trademark Law of 2020 and other related laws of the country.

Mission objective of the IPD

The IPD aims to establish the foundational infrastructure necessary for the establishment of IP system, while also developing an IP strategy that can contribute to the State’s socio-economic development. By focusing on ensuring effective protection of IP rights, the IPD aims to foster innovation and creativity, goals include fostering cooperation and coordination with both local and international organizations to improve implementation and enforcement of IP laws. Another key mission objective is to increase raising IP awareness and strengthen capacity-building efforts for the future of intellectual property sector development.

IP Agency

It should be addressed that the set-up of the IP Agency, organized by the IP Central Committee, is a focal point in resolving issues with the applicants who may not be fully aware of the requirements at the time of submission at the IPD for registration. There are individual applicants who prefer to apply directly, without using an IP agent who has attended courses on IP applications held by the IPD. As the procedures are lengthy and not similar to the old filing system, there could be delays due to multiple corrections required in the applications.

Conclusion

It is very much hoped that this basic highlights of the Myanmar Intellectual Property Laws of 2020 will give an idea and a glimpse of what Myanmar has gone through the years of conforming to the TRIPS Agreement and becoming the last ASEAN country member to have the IP laws in place. The Intellectual Property Department, finally under the Ministry of Commerce, managed to hold international-level conventions to introduce our laws, which are still in infancy but strong enough to encourage local inventors and safe for business investors worldwide to invest in Myanmar, where they can enjoy the protection they need.

It is also the responsibility of communities in the international trade to assist and give a chance to underdeveloped countries and help them join IP associations worldwide, attend conferences made affordable to the new generation and publish books in all forms that can easily be acquired at reasonable prices.