Will the UPC become an attractive forum for SEP litigation?

29 February 2024

Photo: Unified Patent Court

The Unified Patent Court (UPC) may become an attractive forum to litigate Standard Essential Patents (SEPs), as the pressure of a pan-European injunction or a central attack on a European patent(s) may revive stalled negotiations about a FRAND-licence. The UPC is, however, a new court system with new procedural rules, no case law of its own, and judges with a mixture of national legal backgrounds. There will thus be uncertainty on how exactly FRAND litigation will play out at the UPC. This article explores some of the issues that may arise during such litigation.

Will FRAND be litigated before the UPC?

The first question is whether FRAND can be litigated at all at the UPC. When the UPC Agreement was drafted, FRAND was not as important a topic as it is now. The UPC Agreement therefore does not explicitly address whether the UPC has jurisdiction to decide on FRAND issues. The expectation is, however, that the UPC will, in any event, deal with FRAND issues as a defence to an infringement action. Article 32 (1)(a) of the UPC Agreement states that the UPC will have exclusive jurisdiction in respect of actions for actual or threatened infringements of patents and supplementary protection certificates and related defences, including counterclaims concerning licences”.

There seems to be no basis for the UPC to decide on FRAND as an independent claim, whether this would be a declaratory action that a patentee or implementer acted in compliance with its FRAND obligations, that a certain set of licence terms would be FRAND, or an action to have the UPC decide the terms of a FRAND licence.

If, however, a FRAND defence is raised as a defence to an infringement action, the SEP holder may ask the UPC to grant a UK-style FRAND injunction, where an injunction is granted unless the implementer accepts a FRAND licence as settled by the court. The court may grant injunctions, but it is not clear whether this would then also encompass the granting of such conditional injunctions. The UPC Agreement is silent on this, so one could argue that a procedural basis is lacking. If the UPC would nevertheless accept that it can hand down such injunctions, the next question would be which metrics it should use for that.

The legal approach to FRAND

When it comes to the legal approach, we have seen that case law is converging in Europe with a focus on the behaviour of parties. Whether they behave as a willing licensee or willing licensor. The framework as set out in Huawei v. ZTE is thereby used as guidance. The national courts of the major European patent jurisdictions agree that this framework should not be seen as a strict set of rules. We would expect the UPC to take a similar approach to FRAND, albeit it being unclear on which legal concept it will be based. The German courts, for example, focus on competition law (Art. 102 TFEU) and the limited case law in Italy suggests that the Italian courts do the same. On the other hand, the Dutch courts have so far kept it open whether the fact that the patentee has a dominant position and there is an abuse thereof is the most relevant consideration. Instead, the Dutch courts mainly focus on the concept of willingness through the lens of precontractual good faith. Should the UPC focus on competition law, it can apply EU law (Art. 24 (1)(a) UPC Agreement), but if it wants to rely on a legal concept such as precontractual good faith, it will have to rely on national law (Art. 24(1)(e) and Art. 24(2) UPC Agreement). Article 12 of the Rome II Regulation then states which law would then be applicable. Since parties will oftentimes have not yet agreed on the law that would be applicable to the licence, this may lead to a debate as well. For ETSI standards, the FRAND declaration is made pursuant to French law (Art. 12 of the ETSI IPR policy), it may be that French law would be applicable (Art. 12(1)(c) of the Rome II Regulation).

Although case law is converging, differences remain. For example in Germany, the implementer is still able to improve its position during proceedings by making improved counter-offers, whereas the Dutch approach is that the implementor cannot. The relevant question in the Netherlands is whether bringing the action for an injunction and/or recall of infringing products was FRAND. So until the UPC’s Court of Appeal decides on the specifics of FRAND, differences between the UPC divisions may remain. It is thereby noted that in major jurisdictions the local divisions will have two local legally qualified judges (out of three), so the local view is likely to be dominant in the beginning.

Procedural considerations

Differences may also exist when it comes to important procedural considerations, such as the disclosure of licences, the speed of proceedings and automatic injunctions.

Disclosure of licences

An important aspect of FRAND proceedings is the disclosure of comparable licences. Owing to disclosure, this is standard in UK proceedings, but also German and Dutch courts have developed a standard practice that at the request of parties, the court orders both the patentee and implementer to disclose their comparable licences. Also, in France the Paris Court of Appeal has ordered the disclosure of some terms of comparable licences in the proceedings between Conversant Wireless and LG.

Article 59 of the UPC Agreement also gives the UPC the possibility to order parties, or even a third party, to produce evidence, subject to the protection of confidential information. Rule 190 of the UPC Rules of Procedure further specifies that the requesting party should first present reasonably available and plausible evidence in support of its claims and specify the evidence which lies in the control of the other party or third party. It also specifies that for the protection of confidential information, the court may form a confidentiality club, limiting the disclosure to certain named people. These are all discretionary powers of the UPC, so also here differences in approach between the divisions of the UPC may be expected.

In the Netherlands, it is currently standard practice that the disclosure of licences is limited for use in the proceedings only. In-house persons who have a commercial role are also excluded from access. At least the Munich district court has taken a similar approach when allowing the disclosure of licences in Germany, but it is questionable whether German procedural law allows for such limitations. In the French proceedings between Conversant Wireless and LG, disclosure was limited to lawyers only. In the recent UK Interdigital litigation, the UK court took a more liberal approach and also allowed access to a broader team of people for the purposes of negotiating a licence / settlement. Since the lack of transparency due to confidentiality provisions in the licences is often perceived as the biggest barrier between parties to reach a FRAND licence, this approach by the UK court may provide parties with the opportunity to reach an agreement without further litigation. It will be interesting to see whether the UPC judges will make use of these discretionary powers to order parties to disclose licences, and if so how they will do it.

Speed of proceedings

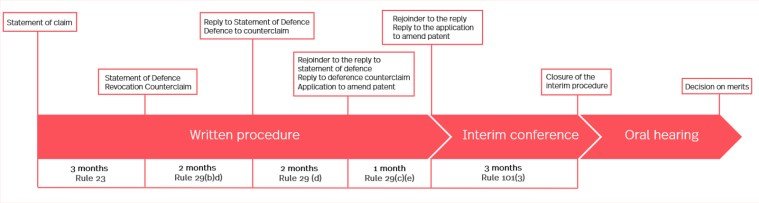

The Rules of Procedure for the UPC were drafted to ensure that they provide for quick and efficient proceedings. They are front-loaded for both claimant and defendant, and provide for two written rounds of pleadings for each party for both a main claim and a possible counterclaim within a period of eight months. The aim is for formal pleadings to last 11 months, and a decision would normally be expected in about a year from the start of the proceedings. Infringement proceedings with a counterclaim for invalidity should follow the following timetable:

However, as stated above, both the UPC Agreement and the Rules of Procedure were not drafted with FRAND proceedings in mind in which a parallel FRAND debate would take place in addition to a determination of infringement and validity. If the UPC would order parties to disclose their licences, this timetable is unlikely to be adhered to. The FRAND debate would first need to have a debate and decision on the disclosure of licences, and if disclosure is ordered, the parties subsequently need sufficient time to actually disclose the licences and have the opportunity to have an (economic) debate about the licences and how this ties in with the FRAND obligations back and forth. Some parties may have dozens of licences, which are often complex and difficult to unpack. A proper FRAND debate may thus take more time than the eight months that is now anticipated for the written and interim procedures.

Automatic injunctions

Articles 62(2) and 63(1) of the UPC Agreement allow for discretion to grant an injunction when infringement of a valid patent is found. The UPC furthermore has to take into account that, among others, the Enforcement Directive (2004/48/EC) provides for a proportionality test. The UPC may therefore deviate from normal practice in most of mainland Europe to grant “automatic” injunctions. The question is whether the UPC will do so, and if so, whether it will do so in FRAND proceedings. On the one hand one could say that a European wide injunction may give too much power for the patentee to force the implementer into accepting terms that are not FRAND. On the other hand there is only room for an injunction if a FRAND defence fails, which may render the question whether an injunction is proportionate moot.

Concluding remarks

Although case law in Europe is converging with respect to FRAND, it will be interesting to see how the UPC will deal with this and how the approach may vary between the various local and regional divisions. We do not expect that each of the UPC’s first instance courts will immediately do something that is completely different from the way the judges are currently handling FRAND in their current national proceedings. The new UPC system will provide ample opportunity for discussing different approaches to FRAND proceedings, and in due course the UPC Court of Appeal will have to decide how arguments relating to FRAND will be handled in a uniform way under the new international system.