Nippon Paint (Singapore) Co. Pte. Ltd., and opposition thereto by Warrior Pte. Ltd.

31 August 2021

These opposition proceedings relate to a dispute on the trademarks between an established supplier of adhesive products for industrial purposes (Nippon Paint (Singapore) Co. Pte. Ltd., or the applicant) and a relatively new entrant into the market (known as Warrior Pte. Ltd., or the opponent). The opponent is a Singaporean company which specializes in developing unique waterproofing products and systems aimed to help solve leakage and seepage problems encountered by building contractors. The applicant, however, is the main Singapore distributor and an affiliate of well-known Japanese paint and paint products manufacturing company, Nippon Paint Holdings Co., Ltd.

The opposition in relation to the applicant’s mark is based, inter alia, on the following grounds:

- The applicant’s mark is similar to an earlier trademark and is to be registered for goods or services identical with or similar to those for which the earlier trademark is protected, there exists a likelihood of confusion on the part of the public as per Section 8(2)(b) of the Trade Marks Act, and therefore, should not be registered (confusing similarity ground); and

- The applicant’s mark is in contravention of Section 8(7) of the Trade Marks Act as it is passing off as the opponent’s marks, and therefore, should not be registered (passing off ground).

Confusing similarity ground

In evaluating the confusing similarity ground, the Registrar applied the “step-by-step” test laid down in the seminal Staywell Hospitality Group v. Starwood Hotels & Resorts Worldwide [2014] 1 SLR 911 case. The steps in Staywell may be summarized as follows:

- The first step is to assess whether the respective marks are similar;

- The second step is to assess whether there is identity or similarity between the goods or services for which registration is sought as against the goods or services for which the earlier trademark is protected;

- The third step is to consider whether there exists a likelihood of confusion because of the marks- and goods/services-similarities.

In applying the Staywell test, the Registrar’s findings were as follows:

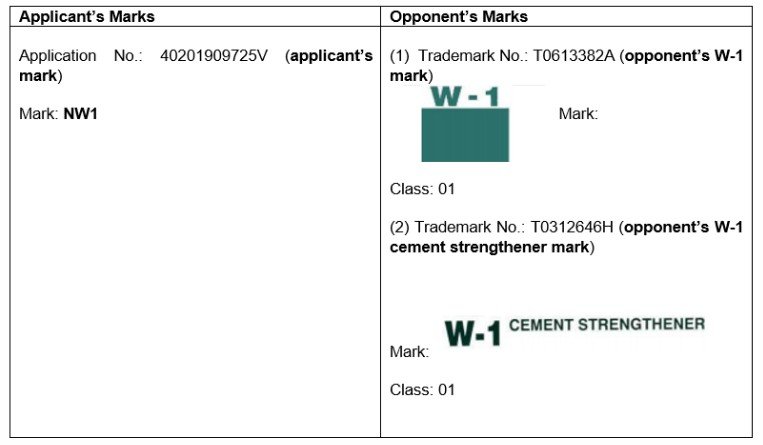

- First, the Registrar found that the opponent’s W-1 mark and the opponent’s W-1 cement strengthener mark are more visually dissimilar than similar to the applicant’s mark. The reasons were as follows:

- The opponent’s W-1 mark had a large rectangle as well as the green color limitation which was not present in the applicant’s mark.

- The opponent’s W-1 cement strengthener mark created a different visual impression created by the length and structure relative to the applicant’s mark.

- Further, the opponent’s W-1 cement strengthener mark contained descriptive terms such as ‘cement strengthener’ while the applicant’s mark only contained the alphanumeric elements “NW1”. The Registrar was of the view that these descriptive terms were sufficient to visually distinguish the marks as wholes.

- Second, in relation to aural similarity, the Registrar found that the opponent’s W-1 mark and the opponent’s W-1 cement strengthener mark are more aurally similar than dissimilar to the applicant’s mark.The reasons were as follows:

- The applicant’s mark will be pronounced as “N” “W” “one” while the opponent’s W-1 mark will be pronounced as “W” “one”. Therefore, the marks were held to be more aurally similar than dissimilar.

- The applicant’s mark is also more similar than dissimilar to the opponent’s W-1 cement strengthener mark as the additional words “cement strengthener” do not modify the aural impression of the mark since the average consumer is unlikely to verbalize the words “cement strengthener”, or if he/she does, the aural impression of these words is diminished to that of “W-1”.

- Finally, in relation to conceptual similarity, the Registrar found as follows:

- The applicant’s mark and the opponent’s W-1 mark were neither similar nor dissimilar from the point of an average consumer. This is because both marks would mean nothing to an average consumer as they would likely have no knowledge on the conceptual derivation of the applicant’s mark and the opponent’s W-1 mark.

- The applicant’s mark and the opponent’sW-1 cement strengthener mark were more dissimilar than similar. This is because term ‘cement strengthener’ “clearly indicated that W1 is a cement strengthener while the applicant’s mark held no meaning to the average consumer.”

Overall, on the basis of the Staywell test, the Registrar found that the average consumer is likely to find the marks more dissimilar than similar. As such, the opposition failed under Section 8(2)(b).

Interestingly, as a postscript, the Registrar did mention that in the marketplace, the packaging of the products can be similar. However, the question of whether the marks are confusingly similar are a different question which should not be conflated with the packaging of the products.

Passing off ground

In evaluating the passing off ground as per Section 8(7) of the Trade Marks Act, the Registrar applied the classic trinity of goodwill, misrepresentation and damage in order to determine if there was passing off on the facts.

In evaluating the same, the Registrar’s findings were as follows:

- On the grounds of goodwill, the Registrar opined that the evidence submitted by the opponent was sufficient to establish that the opponent enjoyed goodwill in Singapore.

- On the ground of misrepresentation, multiple factors were considered, which included:

- The similarities and differences between the application mark and the opponent’s W-1 mark (dealt with above);

- The reputation of opponent’s W-1 mark. The Registrar stated that the stronger reputation of the applicant’s marks points away from confusion as consumers will be able to identify the opponent’s products due to goodwill;

- The normal way in which the goods are purchased. On the facts, the opponent’s marks were usually written along with or close to the opponent’s name and as such, it was not likely to be a misrepresentation as to the source of the goods;

- The nature of the marks. The Registrar was of the view that the opponent’s marks were likely to be seen as a model number which will be associated to the opponent, not the applicant;

- The nature of the goods. The Registrar was of the view that the marks were functional in nature and as such, might cause confusion as to source;

- The price of the goods. The Registrar was of the view that the marks were similar in price and as such, might cause confusion as to source;

- The frequency of purchase of the goods. The Registrar was of the view that since the purchases of the product would be infrequent, the average consumer is likely to pay more attention at the point of purchase; and

- The nature of the consumers. The Registrar was of the view that the average consumer was an expert or a person with some knowledge in the cement industry.

- Amongst the factors considered above, ii), iii), iv) and viii) pointed away from a likelihood of confusion; v) and vi) point towards a likelihood of confusion; and i) and vii) are neutral. Any concerns of possible deception or confusion arising from v) and vi) would dissipate at the point of selection and purchase, when the circumstances considered under the remaining factors would come into the picture.

In conclusion, it was held that the use of the applicant’s mark is not likely to result in retail consumers being deceived or confused into thinking that the applicant’s goods are linked to the opponent’s. As the element of misrepresentation was not established, it followed that there was no substantial risk of damage. Accordingly, opposition under Section 8(7)(a) also failed.

Conclusion

As the opposition had failed on both grounds, the application was registered.