The legal problem of patenting CRIs: Conundrum between technical effect and technical contribution

15 August 2025

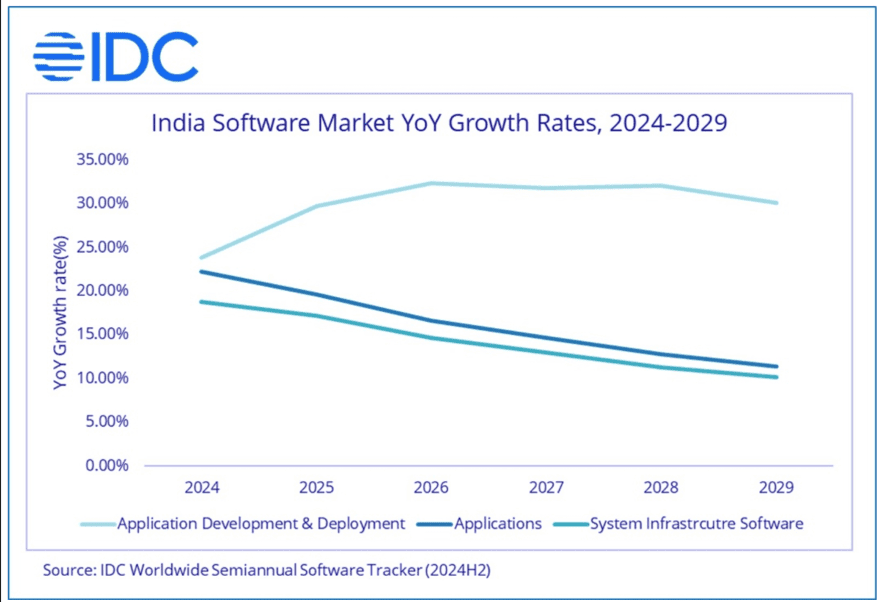

India’s economic dynamism is substantially propelled by its burgeoning software and IT industry. According to the International Data Corporation (IDC), the Indian software industry is poised to attain a market valuation of US$18.4 billion by the close of 2025 and US$35.9 billion by 2029. Therefore, this sector plays a critical role in national economic growth, and its sustained evolution is essential, especially in the age of the transformative influence of artificial intelligence and quantum computing, which is rapidly reconfiguring industrial paradigms and precipitating a surge in patent applications.

Notwithstanding the vibrancy of this industry, securing patent protection for software innovations under Indian patent law remains an intricate and arduous undertaking. The document focuses on the challenges faced by applicants and practitioners in patenting computer-related inventions (CRIs).

Judicial evolution

The basic patentability consideration, as indicated in Ferid Allani v. Union of India was based on a relatively low threshold by identifying a “technical effect” for a CRI implementation that went beyond ordinary interactions between software and hardware without regard to prior art consideration. In other words, the “technical effect” lends a technical character to a computer program, for instance, in the control of an industrial process OR in the internal functioning of the computer itself OR in reducing interference in communication.

However, the legal inquiry for patentability of CRIs has “fluctuated” in terms and concepts while assessing the subject matter eligibility requirement for patentability of CRIs. For instance, in Ericsson v. Lava and Microsoft v. Assistant Controller of Patents, the courts ruled that “a further technical effect” is necessary for determining patent eligibility. Assessing whether a computer program brings about a “further technical effect” involves another level of inquiry but still does not involve a comparison with the prior art. For example, technical effects associated with the data structures used during the operation of a computer system can lead to efficient data processing and storage.

Likewise, the new framework outlined in the CRI Guidelines, 2025 also suggests that the computer program must be “capable of bringing about, when running on a computer, a ‘further technical effect’ going beyond the ‘normal’ physical interactions between the program (software) and the computer (hardware) on which it is run.”

Contrary to the above, in the case of Microsoft v. The Controller of Patents, the coordinate bench stated that an “innovative technical advantage” must be demonstrated and in Raytheon v. The Controller of Patents, the court outlined a two-fold requirement of “technical advancement and technical contribution”, setting a much higher standard for assessing patent eligibility requirements. Further, judgments like Kroll Information Assurance LLC v. The Controller of Patents and Google LLC v. The Controller of Patents have underscored the need for substantial technical advancement in hardware functionality.

Conundrum between “technical effect” and “technical contribution”

The above parallel suggests that a foundational issue of clarity in legal interpretation continues to create persistent ambiguity in defining the precise threshold for patentability, posing a persistent conundrum between the Subject-Matter Eligibility Requirement and the Inventive Step Requirement. Even the legal rules determining patent-eligible subject matter in the new CRI guidelines are not coherent. There is a constant ongoing struggle to clearly distinguish between “technical effect” and “technical contribution” within the legal framework, to indicate a clear interaction between the subject-matter eligibility and inventive step requirements.

When determining whether a computer program provides a technical solution based on “technical contribution”, three essential criteria must be considered in combination: the technical means, the technical problem and the technical effect. For instance, for AI-related inventions, satisfying the “technical contribution” requirement necessitates demonstrating “further technical effect”, such as better computer vision capabilities, more efficient data processing techniques, training an AI model or a novel neural network architecture. Thus, satisfying the requirement of “technical contribution” applies a stricter rule while examining subject matter eligibility of CRIs.

Moreover, the new CRI Guidelines 2025 fail to articulate a succinct legal rule that would coherently demarcate a clear test based on the requirements of “technical effect” or “technical contribution”. The experience of the EPO serves as a pertinent cautionary example for India, which has adopted analogous principles. It was observed that the EPO’s “technical contribution” requirement was found to be “not coherent”, leading to legal uncertainty, and this approach did not prevent particular subject matter from being patented.

Conclusion

While intellectual property protection is a critical component, its direct link to industry development is often nuanced and multifaceted. For India, exploring the current state of patentability for CRIs, including the development of a robust AI-based industry, is crucial for identifying patent policies that encourage, rather than hinder, technological development. However, recent judicial precedents appear to be leaning towards a higher threshold for CRIs, which may not be directly aligned to foster a strong and sustainable software industry in the country. A stricter regime of patent eligibility may be counterproductive and potentially harm the development of emerging technologies, leading to a decrease in patent filings and stifling innovation.

However, the effectiveness of this policy hinges on the clarity and consistency of its implementation. If the judicial inquiry continues to fluctuate in its interpretation of “technical effect” versus “technical contribution,” the intended benefits of the guidelines may be undermined.