Examining the intersection of online fantasy sports with personality rights

28 April 2023

As we immerse in the exponential digital growth in India and internationally, we find ourselves coming face to face with the growing realities of non-fungible tokens (NFTs) and online fantasy sports (OFS) and their intersection with various legal principles. As per a 2022 report circulated by Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu India and the Federation of Indian Fantasy Sports, the OFS market in India has millions of users already and has created thousands of jobs with the possibility to create more employment prospects in the future. It has also paved the way for investment opportunities and new markets through sponsorships as well as partnerships. In 2020, the NITI Aayog, the Indian government think tank tasked with catalysing economic development and fostering cooperative federalism amount the Indian state governments, raised discussions on identifying the OFS space in India and made proposals on how to navigate the relatively new territory of online fantasy sports gaming.

What are OFS games?

OFS games are online sports-based games that enable gamers to create and supervise their virtual teams based on real sportsmen in arrangements set by the game provider. These gaming platforms let users play against each other in virtual matches or leagues based on real-world sporting events. There may or may not be a fee involved to play and the gamers can employ their skill and knowledge to compete within the game. Since OFS games are generally based on real-world athletes, they significantly intersect with the personality and publicity rights of such celebrity sportsmen.

In India, the right to publicity is a legal concept that protects an individual’s right to control the commercial use of their image, name likeliness, voice, and related attributes. The right to publicity has also been analyzed as a part of intellectual property rights, and any unauthorized use of a person’s image or likeness for commercial gain can be subject to legal action. While this right has also been recognized by Indian courts as a part of an individual’s right to privacy and personal liberty, the right to publicity is neither absolute nor part of any statute. In recent years, Indian courts have issued several landmark judgements that have clarified and strengthened the protection afforded to individuals.

The case of Digital Collectibles PTE Ltd and Ors. v. Galactus Funware Technology Private Limited [CS(COMM) 108/2023] as decided on April 26, 2023, is yet another judgment that analyzes this right and its overlap with non-fungible tokens and online fantasy gaming.

Facts of the case

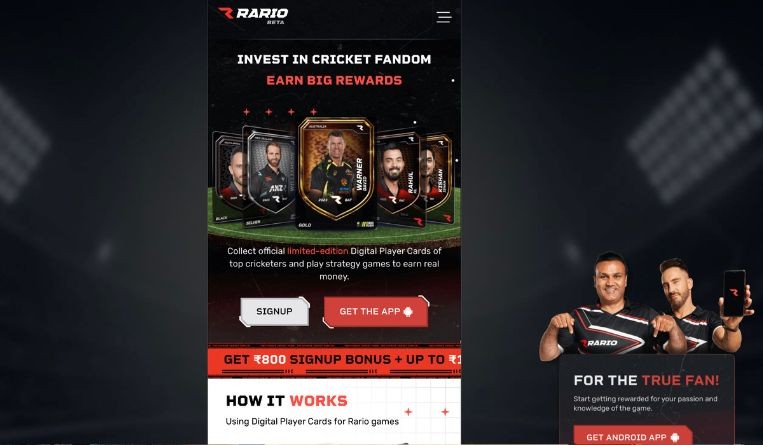

Both parties operate as online fantasy gaming platforms in India. Plaintiff No. 1 is a Singapore-based entity called Digital Collectibles PTE Ltd, operating its business in India. It has created an online marketplace where users can sell, purchase and trade officially licensed “digital player cards” of cricketers. The plaintiff uses a unique software code already embedded in these officially licensed cards (that function as NFTs) which helps identify and differentiate them as authentic and original in the market. Plaintiff No. 1 runs its business under the trade name “Rario” and the Rario website uses the name and photographs of well-known cricket players and other aspects of their personalities. Plaintiffs No. 2 to 6 are the said cricket players who have duly licensed and authorized Plaintiff No. 1 to exclusively use their names and photographs on the Rario website.

Defendant No. 1 operates under the name “Mobile Premier League” and Defendant No. 2 runs a mobile application. Defendants by the name “Striker” got listed on Defendant No. 1’s mobile application. They work under the trade name “Striker Club” and “MPL” on the website and mobile application and have a similar business model as Plaintiff No. 1. Defendants, however, do not have authorization or license from the celebrity athletes to use their names, surnames, initials and images or other attributes of their personality for their business. Defendants use digital player cards with NFTs that include artistic drawings of cricket players. The value of these cards is derived from the names, likenesses and personalities of the players and not on account of the artistic contents of the images.

Rario alleged that it had obtained exclusive rights from these cricketers to use their names and images on digital cards and these rights were infringed by Striker Club. The present suit gave way to discuss the basis and scope of personality rights or right to publicity in respect of public figures or celebrities.

As a part of the reply and submissions, Defendant No. 1 had alleged that Plaintiff No. 1 had concealed the fact that they run an online fantasy game D3 club that is similar to the game offered by Defendant No. 2. They submitted that names and images of a sportsperson are a prevalent and prominent feature of all OFS games that can only be played if all the relevant players are listed and available to choose from and capable of being identified on the platform.

Defendant No. 1 also submitted that in common law jurisdictions such as the UK, celebrity rights exist only in the context of endorsement, which is not the issue in the present matter. Defendant no. 2 submitted while Striker only offers online fantasy games, Rario also offers to buy and sell cricket moments. The NFT cards are only an entry requirement to play Defendant No. 2’s game. It was alleged that the defendants only used information about the cricketers that is already available in the public domain, which is beyond the scope of the personality rights of the players. Further, to play a fantasy game such as this, it is necessary to have included all players to build a team and no impression was given that only a particular player is promoting the game. Lastly, it was also submitted that Striker uses the artwork of the cricketers rather than using real images on the digital cards which are entitled to copyright protection and no statutory provision in India deems to protect the rights claimed by the plaintiffs.

The first intervenor, the India Gaming Federation, also submitted that the “right of publicity” does not have any statutory recognition in India and cannot be created by the court by following principles of common law. The Trade Marks Act, 1999 only recognizes torts of passing off and courts cannot include the “right of publicity” as a part of it. They also mention that in common law jurisdictions such as the UK and Australia, the tort of passing off deals with the misappropriation of the reputation of a celebrity. For a party to claim torts of passing off, it is necessary to show that misrepresentation has been done in a manner so that the rational public believes that the celebrity is endorsing those goods and services as well. They had also commented that the defendant’s cards do not claim that they are officially licensed by the players, unlike those of the plaintiff.

The second intervenor, WinZo Games Pvt Ltd, submitted that rights under freedom of speech and the right to practice profession under the Constitution of India can only be curtailed by way of legislation. In the absence of any statute, the basis for any action for violation of publicity rights must be concerning the tort of deceit, passing off or unfair competition. Just like Defendant No. 2, the intervenor also mentioned that there is no question of deceit or misleading customers and the information of the players in the cards is already available in the public domain.

Court’s analysis

It was observed that the right of publicity is not inherent or absolute in India, solely because of the unauthorized use of a celebrity’s attributes being used for commercial gain. The court mentioned that the use of celebrity names and images for lampooning, satire, parodies, art, scholarship, music, academics, news and other similar uses would be permissible as freedom of speech and expression and would not be considered as the tort of infringement of the right of publicity.

The court further observed that the use of information by online fantasy sports operators regarding player names and data concerning a player’s real-world match performance is freely available in the public domain, which cannot be owned by anybody, including the players themselves. The court also noted that the plaintiff cannot claim to have an exclusive right over the use of NFTs, which are freely available.

Decision of the court

The court dismissed the plaintiff’s application seeking interim relief, stating that the defendants had already been running their business for six months and were in direct competition with the plaintiff. The interim injunction would lead to the closure of the business and a huge financial loss to the defendant.

Far-reaching effects of the judgments

This judgment has some far-reaching effects in this relatively new space where there is a sheer overlap of NFT technology, online fantasy sports, and personality rights. The court accepted that the use of the name and/or the image of a celebrity along with data concerning his on-field performances by OFS platforms is protected by the right to freedom of speech and expression under the Constitution of India. It is a settled position of law that protection extends to commercial speech as well.

The court also accepted that OFS operators use the information of all available players present in the public domain for identification of the players for playing the game. This obviates any possibility of confusion that a particular OFS platform is being endorsed by a particular player or has an association with a particular player. The court also acknowledged that one party cannot claim to have an exclusive right over the use of an NFT technology. NFT is a technology that is freely available. One can use NFT technology to ensure security and authenticity as a means of proof of ownership of its cards and to keep a record of transactions on a blockchain.

As recent as April 6, 2023, after this judgment was reserved in the present case, even the Central Government has notified the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Amendment Rules, 2023, aiming to regulate online gaming through a self-regulatory model and at the same time, provide an enabling framework to navigate online fantasy gaming.