What about memes?

While internet slang is generally too short to be considered a copyrighted work, memes, which usually contains an image with text to bring humorous effect, are more likely to be involved in copyright issues. Vikrant Rana, managing partner at S.S. Rana & Co. in New Delhi, said that before discussing the copyright issues, we should distinguish what types of memes we’re discussing first. “A meme can be of two types. The first type is where the person creating the meme (commonly known as a ‘memer’) uses pictures or videos from original content to create a meme. In such cases, the copyright in the picture would lie with the creator, or if the picture is taken from a movie or a show then the copyright will lie with the producers of the show. Herein, the memer, not being the creator of the picture, is copying it and using the same to depict his content. Therefore, if the producers of the show can prove that the meme infringes upon their copyright, they may be able to stop it from being shared.”

The second type of meme, Rana says, is where the memer has created the meme with pictures and videos, the underlying copyright in which belongs to himself. “A meme like this may be defined as an artistic work made by one's own talent, labour and skill etc., which does not infringe on an existing copyright. However, sharing or reproducing of such kind of memes without prior approval of the memer may be considered copyright infringement, and the creator of the memed picture may be able to restrain others from using it without permission.”

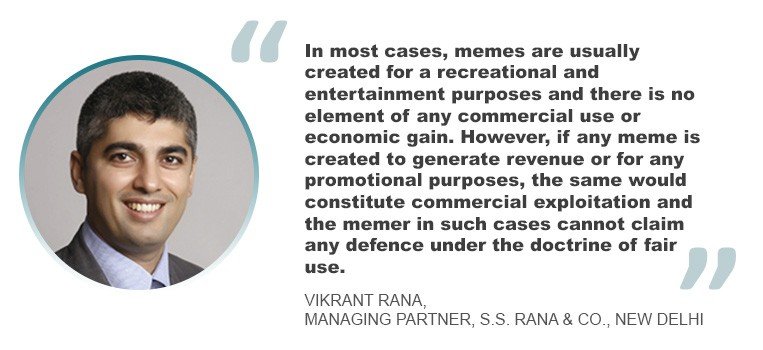

One characteristic of memes is that they are often copied and spread rapidly by netizens – “going viral” as one may say. Then would netizens violate the copyright of the memes by sharing them without approval? Rana explained that memes can be protected under the fair use doctrine, at least in jurisdictions which recognize that legal concept, as India does. To determine whether the use of copyrighted work is “fair” or not, Rana enlisted three factors based on the Indian Copyright Act. The first one is whether the purpose or use of the copied work is of a commercial nature. “In most cases, memes are usually created for a recreational and entertainment purposes and there is no element of any commercial use or economic gain. Therefore, most of the memes satisfy the first factor of fair use doctrine. However, if any meme is created to generate revenues or for any promotional purposes without the required permissions from the owner of the copyright work, the same would constitute commercial exploitation and therefore, the memer in such cases cannot claim any defence under the doctrine of fair use.”

The second factor is the amount and substantiality of the copyrighted work used. “If the memer just takes a single joke or still from an original work such as a television show or a movie, then, a substantial amount of the original work is not copied, and the fair use doctrine can be applied. However, if the original work from which the content is borrowed is a single photograph or any other single frame visual artwork, then it would be considered as borrowing the entire artistic work and constitute an infringement.”

The third factor is the effect on the potential market. “As stated above, memes are usually made for recreational purposes and no commercial gain is expected out of it. Each meme, even though created from a common original work, is unique. Further, even the target audience for the original work and memes are most often different and it rarely affects the viewership of the original works. Therefore, memes satisfy the third factor of fair use doctrine.”

However, there are some exceptional cases in which the fair use doctrine is not applicable. Rana said: “It would be pertinent to mention here that if a meme is intended to harm the society or if it violates the Right to Privacy as enshrined under Article 21 of the Constitution of India, then there is no defence available to meme creator. In fact, the memer cannot even exercise his defence of right to freedom of speech and expression enshrined under Article 19 of the Constitution of India in such cases.”

Rana shared an example to illustrate the Indian courts’ stance that the right to criticize or imitate a person is not exclusive and is limited to the point where the rights of the other person are not affected. “In 2019, the issue of memes of Chief Minister of the State of West Bengal, Mamata Banerjee, had cropped up, wherein the opposition party’s Youth Wing leader Priyanka Sharma had posted morphed images of Mamata Banerjee on social media. The case was taken by the Supreme Court of India, which asked Priyanka Sharma to apologize to Mamata Banerjee for defaming her character. The Supreme Court did not give any leverage to Sharma, even though she argued that she did not ‘create’ the meme and only ‘shared’ it for humour. The Supreme Court in the case held that freedom of speech and expression cannot be denied at any time, but faces its end when such freedom violates the rights of other people.”

Furthermore, in India there are regulations that allow the court to pass a judicial order to identify the meme creator in certain circumstances. Rana said: “The identification of meme creator is one of the critical concerns while stopping defamatory memes or establishing claims of use or infringement of original copyrighted work in memes. To address this issue, the recently formulated Rule 4(2) of The Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021 can be referred to.”

“The provision under Rule 4 while stipulating additional due diligence by significant social media intermediary states that ‘a significant social media intermediary providing services primarily in the nature of messaging shall enable the identification of the first originator of the information on its computer resource as may be required by a judicial order passed by a court’. Hence, if the meme is against the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the state, friendly relations with foreign states etc., then the meme creator or first originator can be identified by the intermediaries (Facebook, Instagram etc.) by a judicial order passed by a court of competent jurisdiction or other competent authorities mentioned in Rule 4(2) of the said rules.”

Rana offered suggestions to meme creators about how they should avoid infringing IP rights of others in India. “It can be safely advised that a meme should serve the purpose of fun and entertainment to the audience without violating rights of any individual and should not be created for the motive of commercial exploitation. Copyright infringement occurs when proper authorization and consent from the copyright owner is missing on the part of the creator of such a meme. It is advisable for young creators to seek proper approvals from the owners of the work prior to utilizing the same. Creation of memes for amusement is fine, but if used for the purpose of business or advertising one should procure necessary consents and license from the copyright owners to avoid facing any kind of legal liability.”

- Ivy Choi